Karen Ingram Vance became the first African American skater to perform with the Ice Capades in 1967 and later performed alongside “Mr. Debonair” with the Ice Follies.

Article Skater Spotlight Tuesday, May 3, 2022

By Jillian L. Martinez

Skating trailblazer Mabel Fairbanks left New York for Los Angeles in the 1940s. The Black and Seminole skater turned coach sought more opportunities for herself and fellow skaters of color to pursue the sport with less racism and prejudice. Over a decade later, up the coast in San Francisco, another Black skater named Karen Ingram Vance would become enamored with ice shows and eventually make her own mark in the sport. In 1967, Vance became the first African American skater to perform with the Ice Capades.

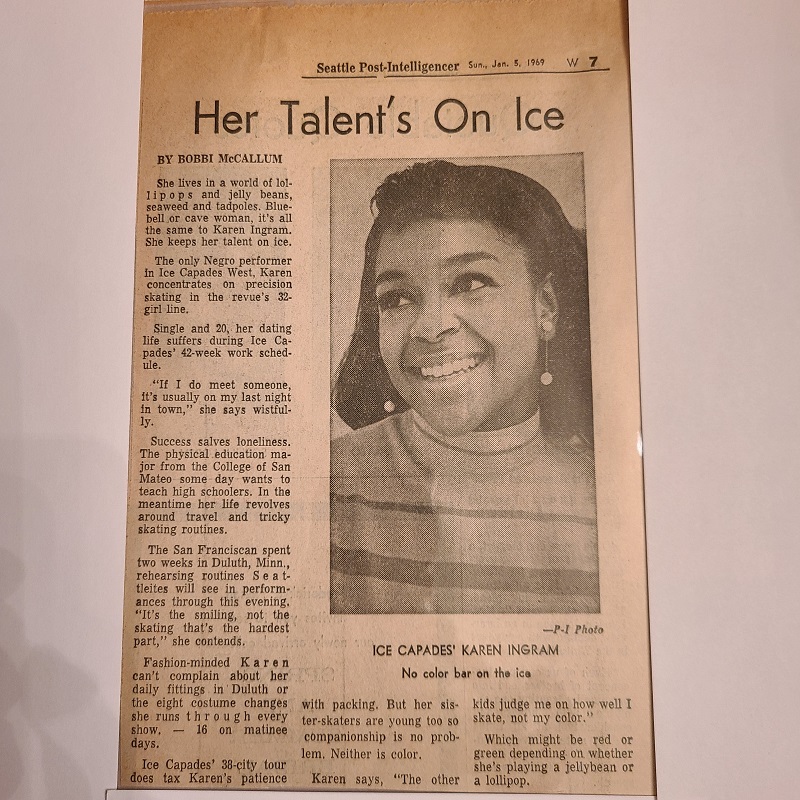

A newspaper clipping highlighting Karen Ingram Vance’s talent on ice.

“Ice Follies used to have a home base in San Francisco, so as a child, my parents would take me to see the shows,” Vance shared of her beginnings with skating. “One day, when I was about 10 years old, I told my parents I wanted to take skating lessons.”

Throughout her childhood, Vance took jazz, ballet and tap dance lessons, as well as cello and violin lessons. When she decided to add skating to her activities, it was purely for fun. According to Vance, she never had goals to become a competitor or a performer. However, Vance naturally took to the sport, and it was not long until skating became more than “just a hobby.”

“The thing was, I loved to skate,” Vance said. “I couldn’t go to the ice rink enough.”

In 1958, Vance had three ice rinks in the Bay Area from which she could choose to take lessons. The Ingram family chose the Phyllis and Harris Legg Skating School, run by the retired husband-wife Ice Follies’ team known for their performances on stilt skates. Unlike Fairbanks, who was denied access to her local rink due to her race, Vance was welcomed by the Leggs.

“Phyllis and Harris Legg were both very genuine,” Vance said. “[Phyllis] was really a warm person and always had a smile on her face. I never felt any prejudice or discrimination.”

In fact, Vance recalls other students of color being enrolled in skating lessons alongside her.

“We had a little bit of everything,” Vance referenced to the diversity of races at the Legg Skating School. Alongside Vance, there were fellow African American skaters enrolled in the school, in addition to Asian and Hispanic skaters.

Uniquely, the Legg Skating School was not sanctioned and, consequently, could not allow its skaters to compete. Instead, Vance and her peers were trained to perform in skating shows. Harris was a record holder in barrel jumping, and Phyllis produced the historic annual Christmas show at the San Francisco Emporium department store. Along with her performances at Emporium, Vance skated with the Leggette Precision Group’s shows at the Cow Palace and Oakland Coliseum before ultimately auditioning for the Ice Capades.

“I was in junior college when I decided I wanted to go into [Ice Capades]. I had seen other girls I skated with go into the show, and I thought I wanted to go, as well,” said Vance, a physical education major at the time. “My coach called Ice Capades; [production assistant] Bill Bain came up from Hollywood; I auditioned and I was pretty much accepted immediately.”

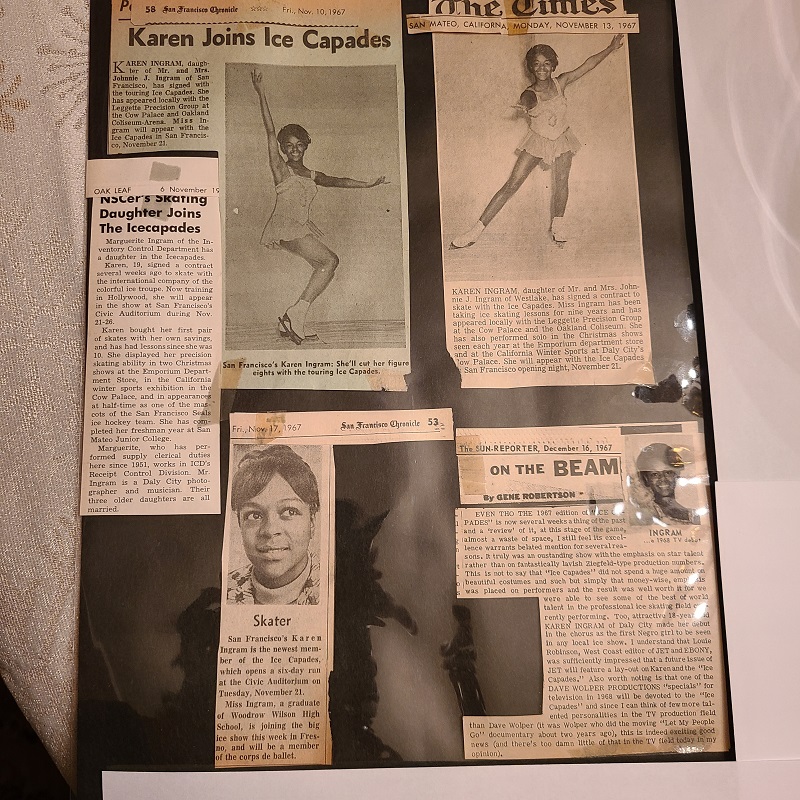

Various newspaper clippings featuring Vance.

Vance made her debut with the Ice Capades on Nov. 16, 1967, at the Fresno Convention Center and gained the attention of the media as the first African American skater to sign to the major ice shows. For nearly two years, Vance was a part of the Ice Capades West family. Together, they toured 38 cities across the U.S. and Canada during the course of 42 weeks.

In 1969, Vance told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “The other kids judge me on how well I skate, not my color.”

Much like her time at the Leggs Skating School, Vance was welcomed and accepted.

“It was an exciting time! I enjoyed the skating, the traveling, the friendships. …Every time I went out [on the ice], I was doing something I loved.”

Tragically, on the evening April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at his hotel in Memphis. When news reached the Ice Capades performers, they were preparing to travel to Little Rock, Arkansas, for their next show. Concerned for the unrest erupting across the nation, the Ice Capades adjusted travel plans to ensure safety for their skaters.

“It was scary because you didn’t know what to expect,” Vance said. “Some of the cities we were supposed to travel through were in an uproar. We flew part of the way and took a bus part of the way. My parents were very concerned and contacted the managers to make sure I would be fine. And, then, my grandmother and aunt and uncle drove from Texas to Little Rock to make sure I was OK.”

Following MLK’s assassination, Vance was on higher alert when traveling and out in public, but she continued to have the support of her Ice Capades peers. In 1969, during her third season with Ice Capades, Vance decided to stop performing with the show. After returning to San Francisco for three years, Vance returned to show business – this time with Ice Follies. Hired by Richard Dwyer, better known as “Mr. Debonair,” Vance performed at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas.

“We were the opening act for [dancer and singer] Joey Heatherton and, later, Diana Ross,” Vance said. “It was really a lot of fun. People treated us like movie stars.”

Once Vance’s contract with Ice Follies concluded, she decided to hang up her skates and make a new career for herself. After her departure from skating, Vance worked for United Airlines for 27 years until she retired as a manager; became a manager at Asian Art Museum of San Francisco; and served as a wedding coordinator. Today, she considers herself “finally retired.” She is a wife, mother and grandmother who loves to cook and drive her grandsons to/from school and their extracurriculars.

“No, I’m not an Olympic skater by any means but I did progress and did quite well. ‘Once upon a time, Karen Ingram was the first Black skater to join a major skating company.’ I did a little something along the way,” Vance humbly said. “I rarely ever skate now. Although, skating will always be in my heart and a part of me.”