Contributor -Feb 17, 2022

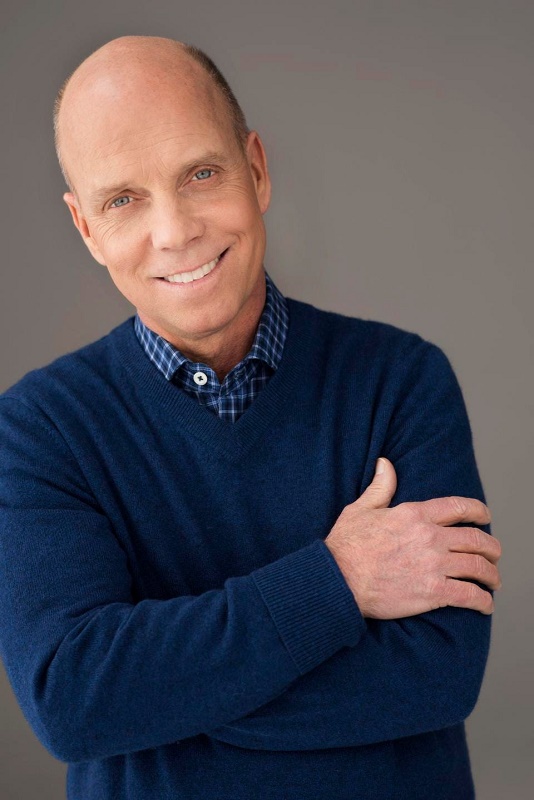

It’s been a dozen years since the United States was atop the Olympic gold medal podium in men’s figure skating. However, last week the clock recalibrated as Yale undergraduate Nathan Chen became the seventh American man to win an Olympic gold medal in figure skating (it is the eighth gold medal as Dick Button won two back-to-back in 1948 and 1952). The 1984 Olympic champion, Scott Hamilton, knows how to end a figure skating drought. When he won the Olympic gold medal in figure skating, it was the first time that an American won the top spot in twenty-four years. The iconic Olympic champion, known for dazzling audience members on the ice with his backflips, shared his incredible story with me.

Adopted at six weeks of age, Scott Hamilton was a very sick child, spending years in and out of hospitals as his growth stunted. Then, plagued by one misdiagnosis after another, doctors gave Hamilton a six-month life expectancy, news his mother refused to accept.

The desire to live a normal life

After four years of sleeping on a chair at Hamilton’s bedside, his parents were exhausted and burned out. A doctor at Boston’s Children’s Hospital saw the toll this was taking on his family and instructed the family to remove Hamilton from all restrictive diets and let him live a normal life. For one morning a week, Hamilton was to play with other children and partake in regular childhood activities. The doctor recommended a new skating rink that recently opened at nearby Bowling Green University.

Thrilled to be surrounded by healthy children, young Scott Hamilton went to the rink and skated with abandoned freedom. The consistency of his training led to improved skating. “Finally, after years of being stuck in the hospital and always being the last person selected for a team,” shared Hamilton, “I was the best in my skating class.” He also got his first dose of self-esteem. He wasn’t just good, he stood out.

Nurturing your talent

Realizing this was more than a passing interest, Hamilton started skating full time. A famous judge saw Hamilton’s potential and recommended he train with Janet Lynn, a renowned figure skater. Having the right coach made a difference as Hamilton eventually made it to the men’s championship. “I skated in front of a packed house and fell five times,” recalled Hamilton. He came in last place. The following year he competed again and only fell twice. His future wasn’t looking bright.

By the time he was sixteen, Hamilton’s mother was diagnosed with cancer, and no money was available to continue his training, but they committed to one more year where he ended up winning the Junior National Title. A couple heard about Hamilton’s dilemma and sponsored his training. Hamilton’s newfound independence, complete with an apartment and sponsor, resulted in him being distracted. He came in ninth place at the next national championships in a disastrous performance. Sadly, that was the last time his mother would see him skate as she died four months later.

Hamilton was at a loss and did not know how to resume without the one person who always had his back and loved him unconditionally. Hoping to honor his mother’s memory, Hamilton decided he would work harder than ever. With a newfound focus, Hamilton returned to his training with an unstoppable mindset. Fearing not trying more than he feared failing, he completed jumps he never could before.

The top spot is in sight

Hamilton soon became fifth in the world. Two of the top five decided to turn professional, and one decided to go to medical school. The top spot was now in view, and Hamilton wanted it badly. There was only one problem. He excelled as a free skater but struggled to perfect his figures– the practice of tracing circles with your blades so precise that leaning on the wrong side of the skate could result in point deductions.

Fall in love with what you hate the most

For years, on and off the ice, Scott Hamilton is a cancer survivor, performer, Olympic commentator, Hamilton decided he was going to find a way to fall in love with figures, the skill he hated most. “The greatest strength is a lack of weakness,” Hamilton shared. Determined to excel at this core skill, day and night Hamilton worked on his figures. He felt he had no choice, as it was the only thing standing between him and a gold medal. Hamilton saw them improving and within time, learned to love figures. He had half the ice for three hours every morning, and he worked non-stop at perfecting this skill. “I knew I had to master this foundational skill if I was ever to win a competition,” exclaimed Hamilton.

In the next event in England, Hamilton came in second place. After that, a four-year winning streak commenced. “In Sarajevo, standing on the top spot on the Olympic podium was a relief,” said Hamilton.

As the exuberance set in, Hamilton realized he was only the fourth American man to ever win an Olympic gold medal in figure skating. His predecessor was not far away. David Jenkins, who won gold in 1960, was now a physician and volunteered to be a team doctor at the 1983 World Figure Skating Championships to make sure Hamilton was supported heading into his Olympic season.

While retired from competitive skating, his love for the sport never waned. He became a fixture in the professional skating shows, was a commentator at numerous Olympic Games, and coaches students at the Scott Hamilton Skating Academy in Tennessee.

After losing his mother to cancer, and a survivor himself, Scott Hamilton, dedicates much of his efforts to the Scott Hamilton CARES Foundation (Cancer Alliance for Research, Education, and Survivorship), which focuses on cancer research and caring for the patient.

More of Olympic champion Scott Hamilton’s story can be found in the books Finish First and The Success Factor.